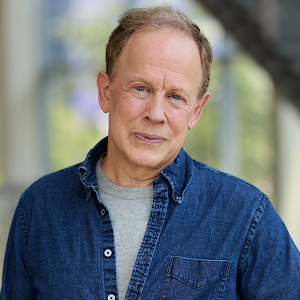

Jim Moorhead is the Founder and CEO of STAND BRAVE, a consulting and coaching firm that helps organizations build empowering cultures. As a former assistant US attorney, investment banker, and law firm partner, he has advised Fortune 500 companies in crises and high-stakes settings. Jim is also the author of The Instant Survivor: Right Ways to Respond When Things Go Wrong. His STAND BRAVE™ framework guides leaders and teams to take calculated risks and respond boldly when faced with adversity.

Here’s a glimpse of what you’ll learn:

- [2:21] How working as a federal prosecutor shaped Jim Moorhead’s understanding of bravery

- [5:41] The role of visualization and mental rehearsal in building confidence during high-pressure situations

- [12:20] How to strengthen bravery through consistent practice

- [21:57] Jim’s STAND BRAVE™ framework for developing acts of courage into a lasting culture of brave leadership

- [31:32] Applying the Instant Survivor crisis framework to daily challenges

- [38:44] Tips for cultivating a culture that embraces difficult questions and ignorance as strength

- [43:17] How to identify and close a bravery gap in organizations

- [51:37] An example of a communications team that embraced brave leadership and outperformed during the pandemic

- [59:05] Jim shares his experience running for political office and losing

- [1:15:40] Prioritizing health, fitness, and good habits to support clear thinking and decision-making

In this episode…

Bravery is often celebrated in hindsight, yet in the moment, it can feel anything but heroic. With organizations facing rapid change and constant pressure, how can leaders and teams act boldly during uncertainty and high stakes? What does it take to build a culture that consistently chooses courage over comfort?

Crisis management and brave leadership authority, Jim Moorhead argues that bravery is not a rare trait but a muscle to be trained. He advises making bravery a shared team value and starting small by openly identifying problems or asking for help before scaling to bigger risks. Leaders can create structures that reward innovation and use clear company values to decide when to walk away from revenue drivers that aren’t the right fit. These habits enable agility and resilience during chaotic times.

In this episode of the Up Arrow Podcast, William Harris sits down with Jim Moorhead, Founder and CEO of STAND BRAVE, to talk about building a culture of courageous leadership. Jim explains why innovation slowdowns are often bravery problems, how his STAND BRAVE™ framework turns single acts of courage into sustained brave leadership, and why taking even one small step can spark a cycle of bold action.

Resources mentioned in this episode

- William Harris on LinkedIn

- Elumynt

- Jim Moorhead: Website | LinkedIn | Email

- The Instant Survivor: Right Ways to Respond When Things Go Wrong by Jim Moorhead

- Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History by Erik H. Erikson

- Outliers: The Story of Success by Malcolm Gladwell

- How I Built This

- “Your Mind Is Hindering Your Growth: How To Unlock It With Optimism & Bravery With Melanie Marshall” on the Up Arrow Podcast

Quotable Moments

- "Bravery is not moving without fear. It's moving in the face of fear and uncertainty."

- "A lot of leaders are struggling because they don't realize that their bravery is on empty."

- "Bravery isn't something you can dictate to others. It has to be practiced, used, and learned."

- "People do brave things despite their fear, and that's what's important to understand about bravery."

- "You have to train yourself in bravery and then position yourself for bigger moments."

Action Steps

- Start small with brave actions: Begin by voicing a concern or asking for help to build confidence. Small acts create momentum and train the “bravery muscle,” preparing you for higher-stakes decisions.

- Reward innovation with tangible incentives: Recognize and compensate employees who propose impactful cost-saving or growth ideas. Incentives motivate teams to surface problems and create a culture where bold thinking is valued.

- Use core values to guide tough decisions: When revenue opportunities conflict with your mission, let your values dictate whether to proceed. This clarity helps teams act with integrity and strengthens trust across the organization.

- Maintain personal health and routines: Regular exercise, good nutrition, and adequate rest support sharper decision-making under pressure. Leaders who care for their physical and mental well-being are more resilient in crises.

- Foster a shared culture of bravery: Invite every team member to participate in identifying problems and proposing solutions. A collective approach spreads responsibility and ensures courage does not rest on one person alone.

Sponsor for this episode

This episode is brought to you by Elumynt. Elumynt is a performance-driven e-commerce marketing agency focused on finding the best opportunities for you to grow and scale your business.

Our paid search, social, and programmatic services have proven to increase traffic and ROAS, allowing you to make more money efficiently.

To learn more, visit www.elumynt.com.

Episode Transcript

Intro 0:03

Welcome to the Up Arrow Podcast with William Harris, featuring top business leaders sharing strategies and resources to get to the next level. Now let's get started with the show.

William Harris 0:15

Hey everyone. I'm William Harris. I'm the founder and CEO of Elumynt and the host of the Up Arrow Podcast, where I feature the best minds in e-commerce and beyond to help you scale from 10 million to 100 million and way beyond that, as you up air your business and your personal life, today's guest knows something, every e commerce founder needs to hear, that bravery is not optional. Jim Moorhead is more than a keynote speaker on brave leadership. He's lived it in the highest stakes arenas imaginable. He's been a federal prosecutor standing just feet away from armed robbers in the courtroom. He's battled through the.com bust as a startup, CFO, stretched VC dollars with creativity like the now famous light bulb Award, which we'll talk about, and advised Fortune 500 companies through moments of crisis when everything seemed to be collapsing. Before that, he cut his teeth on Wall Street as an investment banker at Goldman Sachs, and along the way, he built the philosophy that bravery isn't a one time act, it's a discipline. Jim STAND BRAVE framework helps companies outperform by unlocking brave leadership. Additionally, his book, The instant survivor, has been called a field guide for leaders navigating chaos. So today, we're going to explore what bravery really looks like in e-commerce, how to spot when your company has a bravery problem. How to build a team that acts boldly, and how you as a leader, can model courage when the pressure is highest. Jim, welcome to the Up Arrow Podcast.

Jim Moorhead 1:31

Really pleased to be here. William, thank you. Yeah,

William Harris 1:35

I gotta give a shout out to the magnificent Melanie Marshall, former deputy bureau chief of the BBC, previous guest on the Up Arrow Podcast and herself, quite the expert on bravery as well for making this introduction. Thank you. Melanie. Yeah, she's fantastic. Yeah. Last interruption, then we'll dig right into the good stuff. This episode is brought to you by Elumynt. Elumynt is an award winning advertising agency optimizing e-commerce campaigns around profit. In fact, we've helped 13 of our customers get acquired, with the largest one selling for nearly 800,000,001 that IPO Ed. You can learn more on our website@Elumynt.com, which is spelled elumynt.com. That said on to the good stuff, Jim, you are famed as the bravery guy. But what's the origin? How did you get that nickname?

Jim Moorhead 2:21

Well, I'd say it started with working as a federal prosecutor in the US Attorney's Office in Maryland. And you know, when you're doing that, you have to be brave, not just in front of judges who can ask some pretty sharp questions, but in front of juries and really persuade them to the fact that the defendant that they're watching is guilty of the crimes charged. But I'd say the bigger step too is to really support the witnesses who have to testify. Because testifying, of course, in a criminal courtroom is terrifying, not something that people have done before. They're subject to fierce cross examination, and so getting them ready for that, and having them feel proud of themselves when they testify, and proud of what they're doing was something that really brought me a lot of a lot of you know, personal and professional fulfillment, yeah, but you know, just to stay with you for a moment, I'd say the things you mentioned earlier are what, you know, I've really kind of built a life around bravery. I got a chance to work in other brave places like the US Attorney's Office and Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan and to advise fortune 500 CEOs about how to be brave when facing a crisis, and then also just to lead teams around a brave vision. Because, as you mentioned, Bravery is not optional. If you want to outperform you have to be brave.

William Harris 3:54

Yeah, you brought up the courtroom there a little bit the federal prosecutor. And so I have to ask, I'm sure you saw a lot of crazy things. Was there ever a moment that you were just genuinely a little bit of afraid?

Jim Moorhead 4:07

Well, I mean, not unusual, I was threatened by a defendant. And fortunately, there are US marshals who are in the courtroom, and they understand it's their job to protect everyone, Judge, bailiffs, lawyers in the courtroom. So luckily, when I was physically threatened by one defendant, the US Marshal was there quickly to step in on it. But you know, I'd say, I'd say, you know, you're so focused on what you're doing and you believe in it so much that being afraid wasn't something that was really on the menu.

William Harris 4:46

Yeah, that makes sense. I feel like this came up recently, this summer. I've got some young daughters, and they were at like this, you know, middle school camp out, and one thing was said to one and one thing. Was said to another. And, you know, this turned into this thing where it's like the parents are saying, you know, what was said? What was that? And so we just sat the two girls down, you know, in a coffee shop, it's like, Hey, what's going on? You guys are best friends. What's happening, and the tears flow, even just in that moment, trying to state their position, or whatever, like this is, you know, this is not a federal courtroom. I can only imagine the feelings that people who are in a federal courtroom, you know, up there giving their testimony, might feel. How do you coach them to be able to say what they've said a million times, not in that situation, to be able to still say what they need to be say at that moment?

Jim Moorhead 5:41

Well, I mean, I'll give you one example. There was a witness who was in a bank, and four guys came in with shotguns, and one of them forced her into the vault, and she she testified that she kept trying to position herself away from him, and I asked her why that was, and she said it was because she was six months pregnant and didn't want to be shot in the stomach. Yeah. So that was a traumatic experience for her, and I'd say the way that I got her ready was to, in some ways, make it all real. I brought her to the courtroom where she would testify when it was empty. I role played the kinds of questions she could expect from defense attorneys. I showed her exactly what photographs I would be showing her of the bank. And, you know, because the cameras go off, right? And so they start to reflect what occurred. And she was then in a position, in a way, to be color commentator and say, here's what's happening, here's where I was, here's the gun pointing at me. So I think the fact of giving her the as much comfort as you can of here's what it's going to be like to take her to the real place to get her ready. And she did just an outstanding job.

William Harris 7:16

I like that you talk about even just getting into the right place, because I feel like that's something that we have to do all the time as founders and anybody where oftentimes you can maybe think one thing in one situation, but literally being in a different physical place can change that. I think I've even heard that's true for test taking tests, right? That it's like if you sit in the same seat, you're likely to remember the things that you learned and stuff like that. So I think as founders, there's a bit of truth to that. And even if you can't, maybe get into the same to the physical space that you need to be, but visualizing that as a point can help too.

Jim Moorhead 7:47

Yeah, I spent a lot of time when I was getting ready to make opening and closing arguments of visualizing myself in the courtroom and sitting in a chair that would resemble where it was in the courtroom and standing up and then moving over to speak in front of the jury, and just reinforcing that this was the way it would unfold, in my mind, was, was the way it would unfold in the courtroom.

William Harris 8:13

Yeah, it's interesting. There's a study that was done. I believe it was the Cleveland Clinic, around 2008 and I've shared this before on the podcast, but it's really good, relevant here, where they had patients basically imagine working out, where they would imagine doing these different workouts. And I don't remember the exact extent, but I think it's like eight weeks where they just imagined it, and they showed like, I think it was significant, like 28% improvement in strength in that workout eight weeks later without ever having done the workout in a lot of that was because it developed the right neurons and connections and everything for them to be able to do that. And I think to your point where it's like, the more that we can prepare ourselves run through these scenarios you talk about, you know, there are a lot of people will talk about, it's like, well, in order for you to be successful, you have to visualize the success, and let's say, throw out, you know, any of the stuff that you might say, like, oh, that sounds like too wishy washy. There's something to be said for your body actually wiring the connections that it needs to have in order to be in the right spot. So that way, when you are in the courtroom, it's already gone through the scenario. It's run through, maybe the nerves that you would have had, and it's already learned. Hey, I know how to regulate my body in this scenario now.

Jim Moorhead 9:24

Yeah, just to pick up on that, one of the ways that you try to speed things up to become an excellent trial lawyer in the courtroom is to read books about other trials that have happened and to really learn to see what lawyers did in those situations. And I think the same thing is true for founders of companies, because, you know, they can listen to how I built this, for example, right? And hear how, you know, others got their companies going, or just read in CEO magazine or inc or wherever, right? Because then you. And then you start to see patterns, and you start to recognize when something comes up in your startup. Oh, I remember, that's how that was handled over here. And learn from that. So it's part of that visualizing, as you said, of what's the world around me and how can I react best to it? I love that.

William Harris 10:20

Speaking of reading, I remember you telling me that one of your influences was young man Luther made an impact you when you were younger. What did the idea of why? What age were you when you read that? And how did this idea of brave revolution, kind of, what did it spark in you?

Jim Moorhead 10:39

Okay, so I was in high school. And, you know, this was a book about Martin Luther, and it was done by a psychiatrist really trying to kind of understand Martin Luther, what led him to take such a brave stand against the church and against, you know, its practices of indulgences and and challenge also the idea that in order to have a relationship with God, it had to go through the priests at the front of the church, right that you could have a direct relationship with God, the priesthood of every believer, as they called it. But what struck me was his personal bravery, because he was called in front of the church, he was excommunicated, he was threatened with death, and only a, you know, a royal figure in where he lived, kind of pretended to kidnap him, and then, in fact, shielded him, but he he was unwavering in his view. And so that was extremely impressive. And just was a kind of model, not that anything in my life has resembled something of that magnitude, but we all can kind of play off people who we admire and try to absorb lessons from their life.

William Harris 12:06

No, that's good. I want to shift focus a little bit into frameworks of bravery. You told me that bravery isn't innate, it's a muscle. So how do we work that muscle?

Jim Moorhead 12:20

Well, I think the first thing to do is to really, kind of open up the conversation around bravery. Because, you know, if you think about it, with him, right? We didn't grow up around the table, you know, with our parents saying, let's talk about bravery, or in school or or anywhere, really, right? And so that's not to say we weren't aware of bravery. We would admire people who did brave things and maybe absorb that, but we didn't then think, okay, kind of, how did that happen? And how can I do it? And, you know, the first step is really to hold up the mirror to yourself and to say, Why do I want to be brave? Where will that lead me? What's holding me back from being brave? Who do I look around and see right now that I admire, who I think is brave, and what brave things are they doing? And how could I bring that back to my own situation, whether as a founder of a startup or emerging company, and particularly then the biggest step is to how to start that conversation after, in a way, you have it with yourself, with your team, because at its best, Bravery is a shared experience, and it's a shared culture where all of you are empowered, encouraged, invited to have honest conversations and to point out problems and to suggest better solutions, because if you're looking for growth and innovation, that's how it happens. It happens through the path of bravery.

William Harris 13:55

I think about how you talk about this is a shared experience, and it feels like a lot of times we are more brave when somebody else around us is brave, right? It's almost contagious. If you see somebody to be brave, you're like, oh, maybe I can do that then, too. It seems like this is something that typically is going to start with the leader of the organization, but it maybe doesn't have to. This could start with somebody else on the organization too, right? And maybe encouraging the leader?

Jim Moorhead 14:21

Yeah, that's right. So I think it can, I think it's probably going to start with a team leader, sure, who is going to start this conversation and also start to identify what are brave actions that we want to take and that we will support each other and support our growth individually, but support our growth as a team. And so it's so important to have that shared conversation. Bravery isn't something you can dictate to others. You can't you know it has to be something that, as you said, is practiced. Used and learned and something that people are proud about, because the you know, a lot of people you know, get trapped in myths about bravery. They think, oh, brave people are born brave, or brave people are special, or I'm not brave because my fear of being brave is unique, and we know when that's all baloney, right? People do brave things despite their fear, and that's what's important to understand. Bravery is not moving without fear. It's moving in the face of fear and uncertainty and change, and just maybe one quick thing to add to that. You see, I think a lot of leaders are struggling because they don't realize that their bravery is on empty. And what that means when it's on empty is that they play it safe and they stick with the status quo and they, you know, stick with strategies that are outdated, and the the critical thing is to recognize that, because otherwise, in the absence of brave leadership, your company is going to edge towards stagnation.

William Harris 16:13

Sure, yeah, and I think we see that a lot of times with businesses, and they get to the point, I mean, maybe this is a stretch, but it's like things like Sears or blockbuster, they were unwilling to be brave, unwilling to do something different. It's like, maybe, maybe, realistically, they weren't lacking innovation. Maybe they looked at things and said, we've got some other ideas. I don't know. Let's just stick to what we know and what we're doing. Likely, somebody in the room was had these, some of these other ideas. Somebody in the room was aware of this, but they didn't have the guts to go through with doing something.

Jim Moorhead 16:49

No, you're exactly right. There was a Harvard business review, review piece that talked about Macy's and Sears and Nordstroms, and said that they pursued a timid transformation, and timid won't do the job in today's world, it's too volatile, it's too uncertain, it's too chaotic, it moves too fast, which is why you have to get that bravery, muscle and capability. You know, in action. There was one of our great astronauts, Buzz Aldrin, said that bravery is the gradual accumulation of discipline, and that's the right way for people to think about it, which is, I'm going to start small, I'm going to take some brave actions. I'm going to bring others in my team to do the same thing, and together we're going to move up, then we're positioned to take brave action under bigger pressure and in situations that are tougher. A lot of people think, Oh, I'll be brave when I need to no sure there's a great navy seal line that people default to the level of their training, they don't rise to the occasion, and so you have to train yourself in bravery and then position yourself for bigger moments.

William Harris 18:10

So maybe these are gimmicks, but can you train yourself on things that are not as important, like with this work? Let's say maybe you're scared of spiders or something. You're like, I'm going to go into this room full of spiders on purpose. I'm going to let this spider crawl around on me. Or, or I'm going to allow somebody to pick out any outfit from Goodwill they and I have to wear this all day, right? Like, can you like, they seem small, but can you even do little things like that to begin training bravery.

Jim Moorhead 18:43

Well, you could, but I don't know if you need to go there. Yes. I mean, if you need to get over some kind of phobia like that, I think you can make progress in that way. What I'm really thinking about is we all know that there's a problem that we should point out, or there's a conversation we should have with a colleague, or there's a there's maybe a colleague who you recognize needs some help on something, or maybe you need some help, and so it's brave to put your hand in the air. It's hard for a lot of us to ask for help. So there's a lot of smaller things that you can do to exercise the bravery muscle that then positions you to really to be a brave leader in a bigger way going forward.

William Harris 19:29

Yeah, on your site, you talk about how innovation slow down isn't a strategy problem. It's a bravery problem. I feel like that's kind of what we're getting at here, that it's like a lot of the innovation issues that people are having are not actually innovation issues. These are bravery problems.

Jim Moorhead 19:45

That's exactly right. And I think the the important thing is that you know, you really never know where innovation is going to come from, which employee might produce the idea or group of employees. And oftentimes we we think. About innovation in kind of a top down way. Okay, we'll appoint a chief innovation officer, and he or she will guide the path to innovation. The better way is to start bottoms up and to have everyone feel that they can be part of important path breaking solutions, and if you empower every employee to feel that way, then that maximizes your opportunity for innovation, because you're never really sure where it's going to come

William Harris 20:30

from. Yeah, I feel like this is true in every brainstorm that I've ever been in that you know, you think you have a great idea, and then you get into the brainstorm, and I, you know, as a CEO, I can say that I've done this right, where we bring our leadership team, and I'm like, I'm sure, I'm sure I know where we're going to go, and I just can't wait for the team to come up with the solution of it. Put it up to a brainstorm and go right, darn it. I like that idea even better. This is really, really good, right?

Jim Moorhead 20:59

That's great. That's well. And you know, if we think about in the venture capital context, too, if you ask any honest venture capitalist, they'll tell you, Okay, we're going to make 10 investments, and we know that one or two can be rocket ships, a lot will bounce along the bottom, maybe have some success, and a bunch will fail flat out. But they can't tell you which ones in advance. They just know that the that by seeding a bunch of, you know, companies with promise, there will be success. And I think we can think about the same thing, seeding employees to feel a part of the solution and to invest in them and give them the opportunity to innovate and lead the way.

William Harris 21:45

I like that a lot. You coined the term STAND BRAVE the STAND BRAVE framework, what are its core pillars and what inspired it?

Jim Moorhead 21:57

Well, what inspired it was maybe going all the way back to Martin Luther, because that's what he did. He stood brave under huge pressure. And we won't face that same kind of pressure in our lives, most likely, but we will face pressures big and small. You know, every day, every week, every month. So I viewed it as kind of a rally cry to say this is something that we all want to do and should be ready to do and prepared to do. The framework, really is aiming to have people comfortable being brave first for a moment, as we talked about just the small little actions, right? I'm going to have the hard conversation. I'm going to put my hand in the air and point out a problem. What organizations need, though, is not to just be brave one and done. They need to be brave for a duration of projects, of important initiatives. So that's really the second stage of brave leadership, and then the third stage is really to be brave for a lifetime, because that's where you pick up sustained innovation and and growth. And there's a study done by Appa worldwide, which demonstrates that companies outperform when they have an enterprising or brave culture which rewards candor and curiosity and risk taking and reinvention. But to put that brave culture in place, you need brave leaders who are going to not just say, We want you to be innovative. They're going to give them the opportunities and give them the chance also to fail and to throw their arms around people who fail, and to reward innovation, because people respond to those you know that incentive as well. So what you're really looking to do is to start up people on a small basis, single acts, then through projects and initiatives, and then really a brave culture, which lasts for a lifetime,

William Harris 24:09

that a that, let's say, ability to fail is huge. I'm proud of our team's innovation. That is one of our three core values we have, which is to be to be accountable, to be innovative and to be human. And one of the ways that I try to encourage that on our team is to remind them of something that I actually borrowed from the hospital. So I used to work in the hospital, and as you can imagine, we had what were called sentinel events, which are unfortunately very, very bad things. Somebody amputates the wrong limb, somebody gets the wrong medication and dies. There are some seriously bad things that can happen, and the way that the hospital treated it, at least the one that I was at was it was a no fault reporting system, because the whole idea is, if you're afraid to say what happened, then the process can ever. Change. We can't figure out what this is. This is a no. We just need to know what this is. And similarly, I try to say the same thing to my team, where it's like, as long as there's two things, right, if it was gross negligence, where you just decided to, you know, get drunk and start, you know, changing somebody's ads around, or you did it on purpose, right? As long as it's not one of those two things, then it's a learning opportunity for us. And the reality is, those mistakes will happen. And if you know that, you have that freedom to make a mistake, that I think that allows people to go ahead and be more innovative and try.

Jim Moorhead 25:33

I love that. I love that, you know, just picking up on that in the startup where I was the CFO, we had a rule, which was the only way you get into trouble is if you spot a problem and don't say anything, because, as you said, you need to surface the issues. And that's, that's what allows companies to improve and to grow and to, as you said, innovate more. And if you have that kind of culture where people are continuously putting their hands in the air and saying, not only do I spot a problem, but I've got an idea about how we can do this better, and I've got a solution, then that's the kind of dynamic environment that creates innovation.

William Harris 26:19

It reminds me of something I remember reading in the book Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell, and I think it was something along the lines of, they were just trying to figure out what was going on with certain airlines that were getting in more fatal accidents than others, and they found that it was a culture because of just certain regions where people were less they felt like they were couldn't Speak up to their superiors in a way that would challenge them, and so, out of respect, they allow the plane to crash and die, right? It sounds ridiculous when you put it that way, but like there are certain cultures that maybe don't allow that to happen. But we can go the other way too, where it seems like maybe it's, you know, everything that you suggest is, you know, somebody's got a negative opinion about this or that, like, well, that's wrong. This is broken. We could do better. Blah, blah, blah. How do you how do you make sure you don't swing too far in the other direction of critical feedback, where nothing is now worthwhile?

Jim Moorhead 27:14

Well, I think the one of the ways to do that is to, and we did this at the startup, is to reward positive innovation, and do it with with money. We developed a light bulb award, where we rewarded employees who came up with the best cost saving ideas. And, you know, in some ways, that's, you know, that's the best of American culture, right? It's rewarding innovation. It's competitive. It is, you know, a an open kind of look at the company, right? There's not, there's not closed down. It's not, there's no barriers to, you know, making improvements and so and it also created collaboration, because it wasn't just one person coming up with the idea. Typically, the winners were several people in a team approach. So that was, that was, I thought, something, you know, very special. But if you if you reward positive, innovative uh, solutions. Then you'll hear more about them and see more of

William Harris 28:26

them. I want to learn more about the light bulb moment, because I feel like this is a really interesting idea. Um, can do you remember any of the things that came from this that you're like, oh, this was one that really shocked me, that somebody was able to come up

Jim Moorhead 28:40

with, you know, I unfortunately don't, but I remember being surprised by particularly the first winner, which was, you know, not, I mean, not a massive amount of money, but we were looking to save what we could. And it was $75,000 in something that could be changed, just kind of with a finger snap. And I believe it was, you know, on the on the assembly line, to avoid, you know, problems in the manufacturing process that would waste material, waste, and particularly far along in the process, so that, by stopping things early, you avoided a lot of expense that was put into products that were not going to make it. But no, I was, I was really pleased to have kicked that off, and it particularly in a situation where, you know, there's a lot of pressure in startups right to make it happen and to make it work. And there's, you know, you're under pressure from investors and from the board and from, you know, colleagues, because we're all in right? And so something that's a positive each month to point to and to make people. Proud of was a great moment.

William Harris 30:03

Yeah, did it ever become a burden? Did it ever get to the point where people just like, okay, they're asking us for another idea here. Why don't you figure out the idea?

Jim Moorhead 30:12

Well, you know, I think that that in to be kind of blunt, money helped solve that problem. So, you know, if the reward is always there, and then there's the competitive aspect too, which is why are so and so winning the award. You know, I've got ideas too, so let me put my you know idea in place. So I think the, you know, as I mentioned earlier, kind of the elements of competition and of collaboration and of money, those are pretty strong incentives, plus then you know the pride that goes along with it for being called up in front of the entire company to say, here are the winners.

William Harris 30:50

Yeah, praise in public, right? Yes, in private. How does this differ from the four steps in your book, The instant survivor, you had, stay frosty, secure support, stand tall, save your future. Like, how do these kind of nudge us into this?

Jim Moorhead 31:11

I'm sorry, unpack that for me a little bit. I mean, with the four, you know, the four step framework, yeah,

William Harris 31:17

yeah. Like, how do those you know the idea of, like, staying cool, right? Staying frosty, securing support, standing tall, saving free how do those help us to become brave then as well?

Jim Moorhead 31:32

Oh, well, because the and just just to kind of, you know, unpack that for a moment, that was really, what I had found was a useful framework for companies to work through crisis situations, because the natural reaction is not to stay cool. And so, you know, that's an important first step right? The in some ways, the crisis experience was a little bit backwards. In other words, what I mean is you don't want your first experience to be under huge pressure and so, but that's, that's the situation that I was dealing with and advising fortune 500 and other companies, right? Suddenly, the CEO and C suite was facing huge pressure around a product recall or a sexual harassment scandal or a criminal investigation or class action litigation, you know, whatever it was. And so then they had to, you know, take those steps right of staying cool and securing support and standing tall, you know, and to move through them. So I think the I think the framework is useful and can be replicated for smaller situations, right, the same, the framework still works, right, but it was designed for disasters.

William Harris 33:00

Sure. I think sometimes when I think about things, being able to know how to handle the craziest situations allows me to handle the small situations better. If I can look at this, I say, yeah, stay frosty. Then when you get that mean email from a client, or you get that, you know, nasty message from an employee who's frustrated, or whatever it might be, it's easy to not want to stay frosty. It's easy to want to kind of maybe go off through but if you can look at it from you say, say, Yeah, it feels and I remember Melanie Marshall talking about this, the difference between being shot at in some of the places that she had bullets flying overhead and that mean email, your body almost doesn't recognize the difference, and it can feel the same, because that it just, you know, unlocks this, this, this drive in us to protect ourselves, and whatever that might be. And so sometimes being able to look at this and say, Okay, how do I take this framework for big crises and now use that framework in some of these smaller situations? Okay, I need to. I need to, you know, stay frosty. I need to secure some support. If we can, I look at it and it's like you said to your point, maybe train it in these smaller situations to use that framework. Then when that big framework, when that big things happens, we're already trained to do that.

Jim Moorhead 34:15

Yeah, because I think one of the reasons that people struggle, right, and they're told oftentimes in life, you know, be cool, you know, settle down, so forth. But they aren't told how to do that. And the way really to do it is to have a plan in mind, which is when a problem comes up, to really take a look at it and see what is it, and what's the severity of it, and how can I move on this problem? What's the first action I can take, and who can I get to help me address it? And you know, that kind of thinking isn't what we're, you know, taught in school or, you know, have heard other places. Things, but if you have that kind of framework in your head, then you can move through, as you're saying, William, whether it's a big problem or a small problem, you can use the certain the same framework to move through

William Harris 35:11

Yeah, because going back to preparation, I find that I'm a lot more brave in situations where I've prepared for them, right? You'd like to make sure that you're also going to be brave in situations you're unprepared for. But the way to do that is if you already have, like, this set of tools and process that you're very comfortable with implementing in those situations where you aren't maybe as emotional. So when that thing does happen, you say, Okay, I'm still scared. To your point, bravery, right? Takes place when you are still in fear, but you're like, I'm still feeling this. My body is having a physiological response to this stimulus right now, but I have some practiced behaviors that I'm able to implement.

Jim Moorhead 35:48

You know, I love that. And I'm sure you've heard the phrase William, flexible within a framework. And the beauty of having that framework kind of laid down, and, you know, innate to you is that it then does allow flexibility, because there's no, you know, cookbook response that we can say, you know, in a situation you always do A, B, C, D, E, right? You may have to bounce to F and come back to B and waltz down to Z, and, you know, be flexible, but knowing kind of how the framework can assist you and guide you is central to a better response.

William Harris 36:26

This is one of the biggest reasons why I'm a fan of both sports and music in children, because in both of these you have to be able to run with this. And so I was lucky to have to play basketball, and I was also musician and played in bands and stuff. And in both of these situations, you run the play, but if you just run the play, you're gonna miss the opportunity. And you have to be able to have that flexibility within that. And the same thing is true for music, right? You're playing in the band, and it's like, oh, you know what? They the singer decided that they want to go ahead and go with, you know, a third chorus this time. And so you got to just run with it. And, you know, figure out how you're gonna go with that. And so I think that and so I think that there's some idea where it's like there's a framework, but you can be flexible within that. I've found that the people that I hire that have played sports or been in music or in some other way have already developed these skills without them even realizing it. It seems like they're more capable in a lot of others. And I'm sure there are more ways beyond just sports and music. Those are just two that I identify.

Jim Moorhead 37:23

With. Now, one of the reasons I think you've identified something so important is because it's critical that employees can grow with the company as it grows. And you know a company at every stage has different challenges, different issues, different concerns. And some employees can be great, just at the startup stage, but then can evolve into being leaders and successful employees as it becomes from moves from 50 to 250, 500, and beyond. And so I think the kind of individual you're describing, who has learned to grow and to be flexible and to, in a way, take pride in being flexible. Because what first seems kind of like, oh boy, you know, here we are outside of the plan to roll through that and to, you know, have success outside of a plan, I think is something people are very proud of.

William Harris 38:26

This reminds me of something you and I were talking about before. E commerce leaders often feel very stretched. They've got customers, tech supply, AI, how do they cultivate a culture where saying I don't know or asking hard questions is seen as brave, not weak.

Jim Moorhead 38:44

Well, that's part of the conversation that and they need, I mean, it isn't just a conversation. They need to live that and lead that right and the it can even be a value that's, you know, put up and talked about, right, which is, and, you know, I wrote a piece recently about Satya Nadella at Microsoft, saying we're going to move from essentially a company of nodals to a company of learners. And so I think if you transmit the idea that we're all learning and we're all learning together, and we won't know all the answers, and none of us can claim to and that's fine, and we're operating in a world that's so dynamic that what were the right answers six months ago might not be the right answer today. And we're going to keep evolving and looking forward and supporting each other as we find that and so I hope we can each help each other find the right answers as we move forward. So it's, again, a shared experience, not where there's some command and control approach that's put forward by a leader, because that doesn't work in today's world. Mm.

William Harris 40:00

Hmm, reminds me of something else that I believe was also in the outliers book Malcolm Gladwell. And it's funny, you go through certain books that you you quote a lot, and I haven't quoted this one, and I feel like probably a year, but I'm quoting it twice in the same same episode here. But it talks about, if I remember correctly, people that were trying to do pottery, and they told the one group that it's like, you've got 30 days, and I'm maybe paraphrasing, and I might get some of this wrong, but you've got 30 days to make the absolute best vase you possibly can. And the other group, it's like, just make as many vases as you possibly can within 30 days, right? And at the end of the 30 days, the group that just made as many as they possibly could, ended up making better ones at the end than the one that was like, Hey, you're going to just really make focus all 30 days on this perfect piece. And I think to your point, the more that we practice, the more likely we are to get the outcome that we want. And this is true for creating content. I've noticed it in making the podcast. And anybody who's done anything would say that it's like your first 100 anything sucks, usually, but the more that you practice this, the better you will get at this. And so we all need to be learners. And if that's a part of the culture that's going to be beneficial,

Jim Moorhead 41:12

I love that. I mean, one of the things that we talked a lot about at Goldman Sachs was looking for the pure plays, the organizations, companies that were just focused on one thing, and the fact of being focused on that would mean that continuous improvement, as you're saying, would inevitably occur, and particularly with companies that were passionate about the product and passionate about their people, and that would lead to remarkable innovation and growth, but the focus that those companies had and really the same thing is true for bravery, it's not a value to add, it's a guiding principle to adopt, so that it reinforces all of your other values. You mentioned your three values, those I'd suggest to you would be reinforced and kind of re stamped within the company if they're supported and guided by bravery,

William Harris 42:21

all of them, all three of those would be better values if there's one of my bravery. Completely agree. You are more accountable because you're brave to be accountable. You are more innovative because you have the bravery to be innovative. You are more human because of the bravery to be human. And the way that we describe that is just that idea. It's like we're all having, you know, good days, bad days, et cetera. And so it's like you have the ability to be able to, like, talk to people, ask them questions, be a human being with that. And so you have the bravery to be able to do those, have those conversations. If, if you were going to come into my company, any other company, how would you identify if we have a bravery problem?

Jim Moorhead 43:01

I don't have to identify it. I know you do,

William Harris 43:03

because it's because it's universal. Okay, well, well, okay, what are some signs that somebody has a bigger problem in their company with bravery than than an other company like this is a significant issue.

Jim Moorhead 43:17

Well, I'd say what I've seen a lot is that companies are in love with their cultures, and they will wax eloquent about their culture, how we are so supportive, and we're so, you know, kind, and we're so innovative, we encourage innovation, and those are the ones that I find actually there is the biggest gap between the espoused marvelous culture and the lack of bravery. Because, you know, one of the things I know we appreciate is that it's not enough to be nice, right? If you if you want to achieve in life, you're going to have to be brave, and that means, as we talked about that you will have to truly hold up the mirror to the company and to yourself and to your colleagues, and you will need to make each other uncomfortable, not in a not in a mean way, but in a way that's beyond Nice. And so the cultures that are more kindergarten like and that overweight, how nice we are to each other, are the ones I think that are most at risk of not being brave,

William Harris 44:36

because we already feel those things we're just not saying them.

Jim Moorhead 44:40

Oh, that's right, that's right, that's That's why, just what you talked about earlier, William, which is to give the freedom and the permission to say those things and to do those things which may not work, may fail, that's fine, as long as you know wasn't reckless and stupid, right? But you undertook some. Thing that was a, you know, a good shot to take. Then that's, it's so, you know, self reinforcing, you know, as you talked about, that's the kind of magnetic culture that not only attract talent, but retains talent. Because when people show up and feel they can be heard and be seen and be part of a solution and grow and be noticed and given credit for innovative ideas. Then Wow. It acts as a magnetic force with others in their group, and they can propel each other forward, because also, you know, not everyone, not everyone, can be brave every day, but if you have a team of brave people, then somebody on that team is always doing something brave that day, and that will encourage others to be brave either that day or the next day.

William Harris 45:54

So let's say we start this. Let's say that we have, let's say that you run into a company that maybe has not allowed as much conversation around the idea where, like you said, it might be offensive, right? There are some things that will be offensive. You don't need to say them in an offensive way, but just by the nature of the truth of them are offensive to say, um, how do you begin doing that as a leader, to begin fostering that type of thing in an organization that already hasn't been that way in the thing that I'm seeing in my head is, you know, the boss comes in and says, Hey, I'm just gonna start picking on you guys a little bit. Wouldn't say it like that, but it's like, Hey, you're really struggling with this. You're struggling with this, you're struggling with this. We need to shape it up. Kind of thing. That's like, that might be offensive, right? But that's the wrong way to go about it. How do you begin to foster that in a way that doesn't just put everybody immediately on, you know, on edge there?

Jim Moorhead 46:48

Yeah, no, it's a great question, because one of the reasons, for example, that I always want to start with a keynote address to a company is because bravery isn't something that we talk about and we tend to be mixed up about it, and even uncomfortable talking about it, because we oftentimes think that, you know, a phrase I used a lot on Wall Street, there's a lot of room between zero and 100 people don't think that way. Oftentimes about bravery, they think they're either brave or a coward. But there's a lot of room in between everything's continuum, yeah. So I like to start with a keynote. Beyond that, then I like to work with a company and do an assessment and say, you know, kind of did what I talked about, the tools I give you. Did you put those to work? Did they land, you know, a little bit like the piano teacher. Did you do your, you know, practice, yeah. And, you know, I think the but the key really, is to start in the shallow end of the pool and to open up the conversations in a non threatening way, you know, and starting at the team level, just, you know, let's talk about bravery. What's it mean to you? And you know, when have you been brave in your life? And when do you struggle to be brave, and what do you think is holding you back? And who do you admire that you've seen do brave stuff, and why do you admire them? And what would it take for you to be more like them, and really bring up the kind of self awareness and awareness of bravery and what it is and what it isn't, and really identify the actions that are brave, that make sense to the team and that they will want to do, and understand why it's important to do. You know, as we've talked about, just about asking for help and offering to give help to people who look like they're struggling and standing up for employees who may be getting mistreated, and coming up with better ideas and pointing out problems, all those things help employees see that bravery leads to a better Place and is something not that's just talked about, but that each of the team members do, the leader supports, and then that will be self reinforcing. So I think the you know, the key though, is to get everybody in the pool. Because bravery is not a spectator sport. You have to get into the pool and start to start to swim,

William Harris 49:22

so getting into the pool, right? The boss being the one who's saying you're doing, you're doing, you're doing that's not brave. The boss saying, I need the feedback. That's a lot more brave, or at least a better way to begin starting that conversation and allow that. How do you feel about anonymous feedback? Then in this situation, because it's not very brave to be able to say everything you possibly can think of when it's anonymous. It's maybe a very, very, very infinitesimal way of starting that feedback process. But versus just saying, hey, I need you, you to actually come through, let's say maybe on the leadership team, you know, not opening it, I need you to tell me, what am I doing wrong? What am I doing right? Give me the actual feedback you. Yeah, as opposed to Yeah, I think Yeah. I think

Jim Moorhead 50:04

I would be a little hesitant to go there first, because it kind of ties back to what you were talking about earlier, which is, if you get people focused on the hole in the donut, that's where they'll spend their time. And so certainly starting into bravery, I'd want them to focus on the positive aspects and how it makes them feel. And haven't they noticed that some of their proudest moments in their life are when they've been brave, and so bring bravery up as a positive shared experience that they can have together, and I think that then can still open up those conversations and the feedback that's so important. But then I think if, if you in some ways as a leader, if you've said, we're going to be brave together, and that will work, you know, kind of two ways, and it'll work with our clients and our customers too. We're not going to just be brave under the roof. We're going to be brave and how we interact with our customers and clients. That's that's a vision that your team can rally round. And then I think that opens up more naturally. The conversations which going forward, probably don't need to be anonymous. Then you can really have that kind of, you know, shared back and forth, as long as the leader is ready to, you know, step up and hear it.

William Harris 51:22

You said that bravery can take you to a better place. Is there an example that you can think of where a team implemented this bravery framework within their business, and it clearly had a monetary difference in what they were doing?

Jim Moorhead 51:37

Yeah, I'll tell you about a team that I worked with at a communications firm, and we collectively put together a brave vision and really rallied around it. And the idea was to be brave with each other, and particularly brave with our clients, and leading them to be brave. And during the pandemic, there were, you know, a lot of parts of the organization which, you know, came under pressure. Ours outperformed. We didn't lose anybody. In fact, had to hire more people because we were so busy. And I think that's because we were being brave. We were being brave and how we, you know, and it made it, it made it, you know, as I talked about earlier, magnetic for people to stay, and we could attract great talent, and our customers could feel that and experience that bravery with us, because we were showing them how to be brave. So it was a kind of virtuous cycle that led to higher revenues.

William Harris 52:48

I like that. How about the flip side of that? Can you think of a moment where bravery was missed in an organization, one that you know could be a public one, right? Something that you've seen where you're like, they, they missed it.

Jim Moorhead 53:05

Well, I think we talked about the big department stores. Yeah, that's a good that missed it. You know, I'll give you an example. And this is a very small thing, but I think it's, I think it's important, which is, you know, in my own case, there was an assignment to help a company in a crisis, and it was overseas, and we had an employee who was on the ground overseas, and the client said, We don't want to work with your representative who's In Country. Well, that was the position, the person best positioned to understand their situation give advice about how to address it. Right? We could have ideas from, you know, the US, but that wouldn't necessarily, you know that those kind of ideas wouldn't be tailored to their country and situations. So it's something where, in retrospect, we should have just said, well, we can't do the work then, and not tried to do the work. And I think a lot of companies can get themselves into trouble when they either don't have the capability or aren't able to use all of the resources that they need to to address a situation, and it takes bravery to pass on revenue and to say to a client not going to do that, we can't support you in the way you're looking for so we're out.

William Harris 54:39

I love the way you worded that bravery can sometimes be not a do, but a not do. How do you know which one is the brave action? Because in this situation, I could say that there could be somebody on either side that could say, the brave thing is to take on the client and say, we're going to figure it out, because we are brave and we will know. We could figure it out. And there's also the bravery that says we are going to figure out how to make do without this revenue. Both of these are brave actions. So how do you decide which one is the brave action and which one is actually still, actually fearful, right?

Jim Moorhead 55:14

Well, I think the you know, they say that every crisis is a values test, and this is a mini crisis, but it's really still a values test. And I think the value that organizations should stand behind are we're going to do our best work and not have any limits on that, and know that that will then produce satisfied clients who will be good referral sources who will be pleased with our work. And to me, it wasn't really a close call on this, because Sure, we might lose some revenue if we had decided not to do the work, but doing it, we were hamstrung and so and we told the client, you know, we'll continue to try and help you, but you're not getting the best from us. So, you know, we picked up the revenue and we did as good a job as we could, but it wasn't the sterling job that we could have done with the help on the ground.

William Harris 56:23

I like that you brought it back to values. In my early days as an entrepreneur, we didn't have your mission statement, core values. It's like, you know, the mission state was just get stuff done, right? Like that was it. That was what we do. And I didn't realize how valuable it was until a mentor of mine told me repeatedly that I needed to implement Eos, that I needed to, you know, EOS traction, and read the book traction. And once we did, I saw how valuable those that mission was, and those values were that they're not just some, you know, ethereal thing out in the distance that mean nothing. It's easier to be brave when you understand why you're being brave, if there is a mission. And to your point, too, it's easier to know which bravery which decision is the right decision, if you have those values there, and you can say, hey, one of these things aligns with my values, one of these does not align with my values. Therefore the brave decision is to do the one that is aligning with my values, that is the bravery.

Jim Moorhead 57:27

And by the way, it is so powerful when you do that, because everyone is watching under the roof. They're watching to see are the are the values just words on walls, or are these things we stand behind, that we stand up for, that we live and your customers and your other stakeholders are watching too to see whether you live up to these values that you have laid down, and particularly, you know, under pressure, as I mentioned, every crisis as a values test, and then people particularly watch to see well, you say that you believe in continuous improvement. Are you really showing it to us? You say you believe in safety. Are you showing us that you know what are you? What are you showing in terms of how you live in responding to a crisis

William Harris 58:24

you have. You've seen a lot, from.com you know, CFO startups, to federal prosecutor, I think that I read there's even a political race maybe thrown in there. Um, you, you've seen a lot, you've been through a lot. Was there ever a moment in your own life where you were maybe exceptionally bummed out? Isn't the word I want to say that you really needed to dig in deeper into bravery than others, where you're just like, I'm not sure, I'm not sure I can get through this.

Jim Moorhead 59:05

Well, yeah, I'd say in the you mentioned about running for political office, I ran for statewide political office, as they called it. It was an incomplete success, meaning that I lost a few weeks after the campaign was over, the Secretary of State Certified the election results, making me a certified loser.

William Harris 59:30

That's a brutal way to put it. Yeah,

Jim Moorhead 59:33

and that was that was a rough place, because I had poured myself into this campaign because I was then after was over, out of work, had drained a lot of savings in pursuing the campaign, and so that was, I would say, a dark moment, and that's what really led me to rely on the same. One framework to get through this that I advised fortune, 500 and other companies to follow, and that's what led to that book, was that I felt, after I was able to get through it by following that framework, that it was just so important to share that with other people, so that when they ran into problems, they could have a framework to look to and work from, because, you know, we go through life without people saying, here's kind of a playbook for you to follow. We typically will just kind of find our way through it. But it's a lot easier if you have a framework to work from.

William Harris 1:00:38

The older I get, and I'm, I'm 40 this year, so I'm crossing into the place where I can call myself old now, old enough, right? So the older I get, the more I find myself appreciating tradition. When I was younger, it seemed like tradition was one of those things you're just like, This is dumb. This is just because it's how it's always been done. Doesn't mean it needs to be done that way. And there's some truth to again, innovation. There's some truth to that. But the older I get, the more I realize that a lot of traditions are steeped in frameworks. And that's really what they are, is they are frameworks that others have done and tried, and the ones that seem to have succeeded are the ones that have these frameworks. And again, you can have flexibility in the framework, but there's something about this, this idea of it's been tried for 1000s of years, and this seems to be the thing that works generally the best for the most people.

Jim Moorhead 1:01:27

Yes, no, I'm a well, also, the reason I think frameworks are so important these days is because the world is so turbulent and so chaotic and so facing such transformation and such pressures from AI and technology and geopolitical issues, and so it's important to have some stuff to kind of rest on, so that you don't always feel you have to kind of start from scratch and reinvent right. Have something to at least look to as a way to think, Okay, here's how I'm going to move through this. I may need to adjust it, and of course you will. You need to be flexible as you go, but at least you know here are the right questions to ask, and here's where I should bring my focus, and that will help you get into action, which is the biggest problem most people face in a crisis or other problem, is not to take brave action right away, and brave action leads to more brave action and to positive results. And again, is a virtuous cycle.

William Harris 1:02:39

That's something that Melanie and I talked about that I really appreciate my approach to this that I like to think about. There's a Bible verse. It says, Thy Word is a lamp unto my feet and a light unto my path. And the phrase that I always liked about this was that it says a lamp unto my feet. And I remember the first time reading it, maybe not the first time I remember at some time reading that I want to say was maybe in high school, thinking that's a really weird way of saying it, why can't I see the rest of the path, right? But the reality is, oftentimes we can't see the rest of the path. The rest of the path is still completely in darkness, but I can see where thy next step is, and that's all I can do. Is I could take this one step right here. And I have found that in my own life, when I get into situations where I'm fearful, because we all do, and I need to be brave, that just taking a step usually ends up being fine and it could be the wrong step. What's interesting about this, I found, is that sometimes you could take the wrong step, but simply taking the step allows you to be able to be not paralyzed, and to be able to move and redirect if you need to.

Jim Moorhead 1:03:35

Yes, yes. Well, and stay with that for a moment the idea of a lamp, because I think that the great leaders aren't just holding their own lamp. They are supplying lamps to others on their team who help light up the earth beneath them, but sometimes light up the sky and really show what the whole situation looks like, and with more people carrying lamps, that's really what brings a company to life, is that is then a shared experience of seeing collectively, here's where we are and here's where we're going, and here's, as You talked about earlier, the vision we have and the mission we're pursuing.

William Harris 1:04:24

What's interesting is, you get that many lamps together, and all of a sudden you can see a lot more, right? It multiplies that, which is nice. That's right. What am I not asking about when it comes to bravery, when it especially as it relates to, you know, the corporate world and E commerce, businesses and founders, what have we not talked about that you're like? You really need to make sure we talk about this too. Well.

Jim Moorhead 1:04:46

I think we should talk about the fact that, you know, I admire folks who are starting up businesses and trying to grow them, and they're brave. And I think the challenge is to make. Maintain that bravery, because I mentioned about leaders oftentimes operating near empty, and it's because they may have started off brave, but then they've let it disappear under the pressure of, okay, we need to raise more money. We need to we've got this administrative issue, we've got this personnel issue, this competitor has come up with this other idea, and the The kind of day to day moments and pressures step in the way of the brave vision we talked about, and of maintaining and supporting your team to be brave and to take brave actions and have brave conversations. So I think what I worry about for leaders is that they are letting their bravery be eroded or fall away under the pressure of what they're doing day to day, and the problem is then it leaves them and the rest of the team unprepared to deal with the challenges as we talked about of today, is volatility, uncertainty and transformation. So they what I would encourage founders is to keep seeding the bravery. Keep supporting the bravery. Keep talking about the bravery. Keep rewarding brave actions. Keep looking to hire brave employees who will grow with the business as it grows. Make bravery central to what you're doing, because otherwise you're putting yourself and your company at risk.

William Harris 1:06:36

It reminds me of this story about a patient going to the doctor and he says, Doc, everywhere I touch it hurts. If I touch, you know, my chin, it hurts. If I touch my ear hurts. If I touch my nose, it hurts. And the doctor says, you've got a broken finger. It's not that the rest of his body's okay. It's just, you know, quit doing that kind of thing. Um, sometimes I think about this and it's like, okay, they are naturally brave people. Founders, as a general rule, they've proven that they have some bravery, and then, like you said, the pressure maybe gets in the way of some of that bravery at a certain point. Why does that pressure get in the way? What and how can they avoid that getting in the way of their bravery,

Jim Moorhead 1:07:24

like what questions are right? Well, and actually, let's stay with that for a moment. I think one of the risks that founders may face as well is to is to think it's enough for them to be brave and that they can be brave. You know, pioneers at the, you know, front of the wagon train who are leading everyone along the path. That's, that's a mind shift they need to make, which is, no, this is going to be, not a a wagon train led by one person. This is going to be a horizontal line of people moving forward together. So I think the way to to really solve the bravery issue is to take the burden off yourself as a founder and appreciate that others can be brave too, and that you want them to be brave, and that you are going to always be looking to support them being brave. So I think the that's the way to do it, because they will be founders will be swept up in dealing with a variety of issues. Fine, make certain then that you created kind of a brave army, because as the general, you can't do it yourself alone.

William Harris 1:08:48

That's so good, I think that you're exactly right, almost because out of necessity to be the founder, you had to be brave alone, to a point right, you had to create the company. And so there's this mental shift of that you have to get out of this. I have to do this on my own, to wait a minute. I now have a team. I now have others who can be brave with me. That's a critical shift.

Jim Moorhead 1:09:08

Yeah, and also that your success is only going to come by creating a brave team. It's not going to be enough for you to continue to be brave, even if you can do that, which is hard under all those pressures we talked about, but to really propel success, you want bravery all around you. And you know, we can, we can use that analogy you talked about sports earlier. You know you want bravery all over the field, right? Not just, not just at the quarterback position, and in the military, you want bravery at every level, right? Brave generals aren't enough, right? It's brave soldiers in the trenches. And that was really the, you know, the story of success on D Day was that folks who were, you know, put. Tunes got blown apart, right? You you know, different people pulled together, who then were brave in pockets, and, you know, helped breakthrough the German lines.

William Harris 1:10:11

That is the epitome of bravery. I want to get to know the human being, Jim Moorhead as well. You like tennis a lot. This is something we were talking about. Um, who do you think is, if you were going to, let's say, start your own tennis team. You're doing doubles, who is the tennis player that you're saying? I want this person on my team?

Jim Moorhead 1:10:37

Well, okay, I'd make a distinction if, okay, wow. And, and I need to look, I'm going to look kind of in the current moment, back, uh, versus, you know, there's hot players right at the moment, but it's, I think maybe too soon to know what their, you know, future is going to be. So if I'm putting together a team, my singles player is Novak Djokovic, okay, and my doubles team are the Bryan brothers. And the Bryan brothers, you know, one of the most Grand Slam titles playing doubles. And then, you know, had this dream chemistry, right? By being twins. We know how those folks can in tune each other's, you know, moves. Yeah, exactly. So they had this magical, magical connection off the court that they brought onto the court, plus had, you know, supreme talent. But you know, I mentioned Novak Djokovic because he he came into such a difficult situation when he came onto the tour, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal were already in front of him and already winning grand slams. And in the year 2010, just as a data point, Novak Djokovic had won one grand slam, Rafael Nadal had won nine, and Federer had won 16. And then by this year, Djokovic had 24 grand slams, leading the way, Nadal at 22 and Federer at 20 he took over. Wow, he just took over and figured out. And the reason it's relevant, I think, to your founders and other C suite folks is because he got to work and figured out, what can I do for myself, what can I eat? What can I how can I train but also, he held up the microscope to his two major competitors and thought, what are they doing? What do I need to do to not only match up to them, but to beat them?

William Harris 1:12:45

So it was bravery, right? The bravery to say, let's say it's brave to say, I'm not currently number one, but I want to be. That's that takes bravery to admit, because that's right, even even to be at his level, he has likely committed his life to this, even when he only had one right, like this has been in everything. And just say, like, I'm still not number one.

Jim Moorhead 1:13:06

Um, no. And by the way, stay with that for a moment, William, because think how many people who were, you know, top 10, top 20 players, couldn't make that jump. That's a giant jump to think, Wow, here are two giants of the game, and I'm going to play through them, and I'm going to end up with more Grand Slam titles than they have.

William Harris 1:13:27

That's wild. Yeah, that's wild. It to even stick with it is, is, in and of itself, a bravery thing, right? And how many times I would say that we would even get to that point where, like, you said it's like, there's a giant there, and you're just like, it's not worth it. I don't. I don't have the bravery to push through the pain that it's going to take for me to go from here to here. So moving on well,

Jim Moorhead 1:13:50

and not only, I mean, it's the you have to have, and this is what really they say distinguishes Djokovic is a mental belief and a ability to be calm in those pressure moments. He has won a number of matches where his opponent had match points in Grand Slam events, and he would maintain this calm, and at least this outward calm, and, you know, work through those moments that other people wouldn't be able to do.

William Harris 1:14:25

I think it has to be an inner calm too. I don't know if you can make that if you're if there's not some type of inner calmness that's there. Why do you think that he was able to do what so many others weren't?

Jim Moorhead 1:14:40

Well, what he would point to is how he grew up, because he's Serbian. Then he grew up during the war there, and I heard him say that success was his only option, because at one point his father held. Up a $10 note and said, This is all we have. And so he was looked to as the one who would support the family and put it on a different path. And so his determination was just deep and intense.

William Harris 1:15:26

He was able to stay frosty. What is your way? How do you stay frosty? Situation is crazy. There's some right yourself.

Jim Moorhead 1:15:40

Well, you know, I'll tell you, part of it is to, you know, when I'm working with clients on this, is to think outside in, meaning that it isn't important. What I'm thinking what's important is what my clients are seeing and needing, and what they need in a crisis is reassurance, and they need a reassurance that they will get through it and that they can move past it and resume focus on their business. And so what they're looking for from me is to transmit that calm that we were talking about and that confidence and and I do believe that, I mean, you know, it's very rare that a company will be knocked out by a crisis. They may not handle it well. They may not be as brave as I might want them to be, but they will typically get through it if they build up enough of a kind of franchise that protects them, enough of a moat around them. But you know, I you know, I guess partly it's because, having been through, as you talked about earlier, so many of these different situations, I have a confidence, and I'm working from a framework in my head about how to address these situations. And I have a pretty wide span of vision from, you know, having been, you know, on Wall Street and in two major communications firms and in two of the, you know, giant law firms in the country, so that I've just seen so many different situations that I feel pretty comfortable that the path that I'm suggesting that a company take is the right one.

William Harris 1:17:36

One of the things I like asking people about is because you seem like someone who's clearly got a framework for a lot of things in your life. You think through things. You're intentional about, your actions, your words. The name of the podcast, up arrow podcast is a mathematical notation for making numbers way, way bigger than exponents that I'd really appreciate. But the idea is, how are we not just up arrowing our business? How are we up arrowing our personal lives as well? Um, what are things in your own personal life that you are passionate about and have been intentional about improving? This could be relationships, it could be health. It could be, you know, anything. But what are things in your personal life that you've been intentional about outside of business?

Jim Moorhead 1:18:19

Well, you know, it's interesting. I would say a good deal of what I've done outside of business has been a desire to perform at full tilt, and so that means, and by the way, that's partly because that's what you know, my clients have needed, and that's what my, you know, family is needed. And so I have looked after my health very carefully. I have, you know, eaten well, you know, stop smoking long time ago, don't drink and and then also, I'm very conscious about exercise, playing tennis, getting to the fitness center, lifting cardio. And by the way, I'm not going to suggest that, you know, I can do, you know, 50 pull ups or, you know, anything crazy, right? But sure, it's just a desire to do, partly because, you know when I was doing crisis work full time, you never know when it would happen. So, you know, I couldn't get caught on a down day. I needed to be ready to go, like kind of as a first responder, and so it couldn't be no time out. I'm not feeling that great today. Check back with me tomorrow, right? You had to be good to go. And so I wanted always to be in a position to be able to, as I say, on the street, hit the bid.

William Harris 1:19:52